Also called DNSpionage

On Nov. 27, 2018, Cisco’s Talos research division published a write-up outlining the contours of a sophisticated cyber-espionage campaign it dubbed “DNSpionage.” We will introduce what happened and how it happened.

Before all, we have to present the main lines of DNS principles. Let’s take an example: We consider that we live in Toulouse during the ’90s and we want to go into a new video store that opened last week. Because we do not have any GPS nor root planning tools, we have to do it with our good old road map.

The name of the Video Store is “Vid’O”, but we do not know where it is. To find the address, we will call a friend and ask him “Do you know where it is ?” and hopefully he will know the location. Because he is a trustable friend, we trust his answer and go where he told us. This is how a DNS (Domaine Name System) works. Replace the “Vid’O” by www.company.fr and the location by an IP address (e.g. 172.16.254.1). If you ask to a DNS what is the computer behind www.company.fr, it will respond you an IP address. This is what you should understand. This how you can navigate to a domain name on the internet, otherwise it would be necessary to juggle with IP addresses, which is infeasible. DNS serves as a kind of phone book for the internet by translating human-friendly Web site names (example.com) into numeric Internet address that are easier for computers to manage.

And…what if our friend is misleading us?

Nice question! What if the person behind the phone is not our friend? What if it is his brother, a villain brother that already was in jail. Unfortunately for us, he has the same voice than our friend. We can not differentiate them. His brother can easily mislead us by giving a false location. When we arrive at the given place, the market is there, we expected that, but what we weren’t aware of, is that this false shop will steal our credit card’s information.

The same can happen if you’re browsing on a website that is not the real one. It’s really easy for an attacker to copy a website and because we trust the website, we will log in, give our credentials, even probably enter our banking information.

What does it have to do with this attack?

Everything, because what attackers did here is they changed information in the DNS records, accessed to the register and changed the target location. They replaced addresses to other addresses that targeted malicious website. Therefore, when you asked “where is example.com?” and the resolvers responded “154.32.54.12” - you had no other choice than to trust him.

After that, attackers took patience to get credentials and information from users that connected themselves. This is a DNS Hijacking. because they subverted the resolution of the Domain Name System queries. They directed the victim to a malicious website and got everything they needed.

How did they do that?

This is the less clear part because there’s a lot of supposition around it - but no certain idea.

According to FireEye report, they had three possible way to accomplish that:

- Technique 1: DNS A Records (attacker logs into the DNS provider’s panel, utilizing previously compromised credentials)

- Technique 2: DNS NS Records (attacker exploits a previously compromised registrar or ccTLD (Top Level Domain that manages .com for example)

- Technique 3: DNS Redirector (based on previously altered A Record or NS Record)

As FireEye notice, it’s difficult to notify a single intrusion vector for each record change, and it is possible that the actor (or actors) is using multiple techniques to gain an initial foothold into each of the targets described above.

They believe at least that some records were changed by compromising a victim’s domain registrar account (highly probable through phishing). When they gained access to the account of each domain name’s registrar, they were able to change the IP where the domain name is pointing to.

Yet, we can’t define them as a DNS attack nor a DNS poisoning, because attackers don’t use the DNS protocol.

What did they get?

When they had access to all traffic, they easily were able to do:

- Direct collection of data from web traffic to affected domains

- Collection of credentials from captured traffic for use in obtaining access to networks of future targets

- Delivery of malware from actor-owned infrastructure

- Create a Let’s Encrypt certificate (which is a free way to get an SSL/TLS certificates) that allowed them to have the HTTPS and make their site more trusted.

The username, password, domain credentials are harvested and stored

Concerned services

28 ORGANIZATIONS IN TOTAL CrowdStrike, a security firm that did a report on this event, have listed all services affected. According to them, there are in total of 28 organizations in 12 different countries. The organizations were primarily located in Middle-East and North Africa region, but there were also limited affected entities in Europe and North America.

Behind the attack, hackers succeeded in compromising key components of DNS infrastructure for a wide number of companies and governments agencies including targets in Albania, Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

Mostly, concerned sectors are government, insurance, civilian aviation, infrastructure providers and even internet service providers:

MOST NOTABLES:

nsa.gov.iq: The National Security Advisory of Iraq

mod.gov.eq: Egyptian Ministry of Defense

gid.gov.jo: Jordan’s General Intelligence Directorate

shish.gov.al: the State Intelligence Service of Albania

Governmental institutions:

webmail.mofa.gov.ae: email for the United Arab Emirates’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs

mail.mfa.gov.eg: mail server for Egypt’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs

embassy.ly: Embassy of Libya

owa.e-albania.al: the Outlook Web Access portal for the e-government portal of Albania

adpvpn.adpolice.gov.ae: VPN service for the Abu Dhabi Police

mail.asp.gov.al: email for Albanian State Police

owa.gov.cy: Microsoft Outlook Web Access for Government of Cyprus

webmail.finance.gov.lb: email for Lebanon Ministry of Finance

Internet services provided affected:

mail.cyta.com.cy: Cyta telecommunications and Internet provider, Cyprus

Companies:

mail.petroleum.gov.eg: Egyptian Ministry of Petroleum

mail.mea.com.lb: email access for Middle East Airlines, which is an airline company.

mail.dga.gov.kw: an email server for Kuwait’s Civil Aviation Bureau

CrowdStrike in its report published some IP addresses used by the hackers to hijack information:

Who did this?

Actually, nobody can tell who did that FireEye’s expert exposing that this activity is conducted by persons based in Iran and that the activity aligns with Iranian government interests.

You can see FireEye arguments on their report, available on their website. What they put forward:

FireEye Intelligence identified access from Iranian IPs to machines used to intercept, record and forward network traffic. While geolocation of an IP address is a weak indicator, these IP addresses were previously observed during the response to an intrusion attributed to Iranian cyber-espionage actors. The entities targeted by this group include Middle Eastern governments whose confidential information would be of interest to the Iranian government and have relatively little financial value. On another side, CrowdStrike’s expert are noticing that even if it’s still a possibility, there is currently not enough information to make any definitive assessment around country or adversary-level attribution at this time.

Is it a new type of attack?

Actually not, there are already some similar attacks that occurred out there, these attacks against the domain name provisioning system are very common and it has nothing to do with DNS poisoning:

- In 2017, Attack on Wikileaks DNS (src)

- In 2016, Canal+ a French premium television channel, see src (only for French readers).

- In 2016, Meteo France, French national meteorological services, see src (only for French readers)

-

In 2013, The New York Times web site was taken down by DNS Hijacking (src). Different operandi, but using a DNS Pharming attack (and not through domain name provisioning system). The attack consists to infect the victims with malware and change the local host file that will redirect him where the attacker wants to.

- In January 2005, Symantec reported a drive-by pharming incident directed against a Mexican bank in which the DNS settings on a customer’s home router were changed after receipt of an e-mail that appeared to be from a legitimate Spanish-language greeting card company.

- In March 2010, requests from more than 900 unique internet addresses and more than 75,000 e-mail messages were redirected, according to log data obtained from compromised Web servers that were used in the attacks, says PC Mag.

How to prevent it?

Let’s see what are actually the best practice given by John Crain is chief security, stability and resiliency officer at ICANN. the non-profit entity that oversees the global domain name industry:

“A lot of this comes down to data hygiene,” Crain.

For large organizations

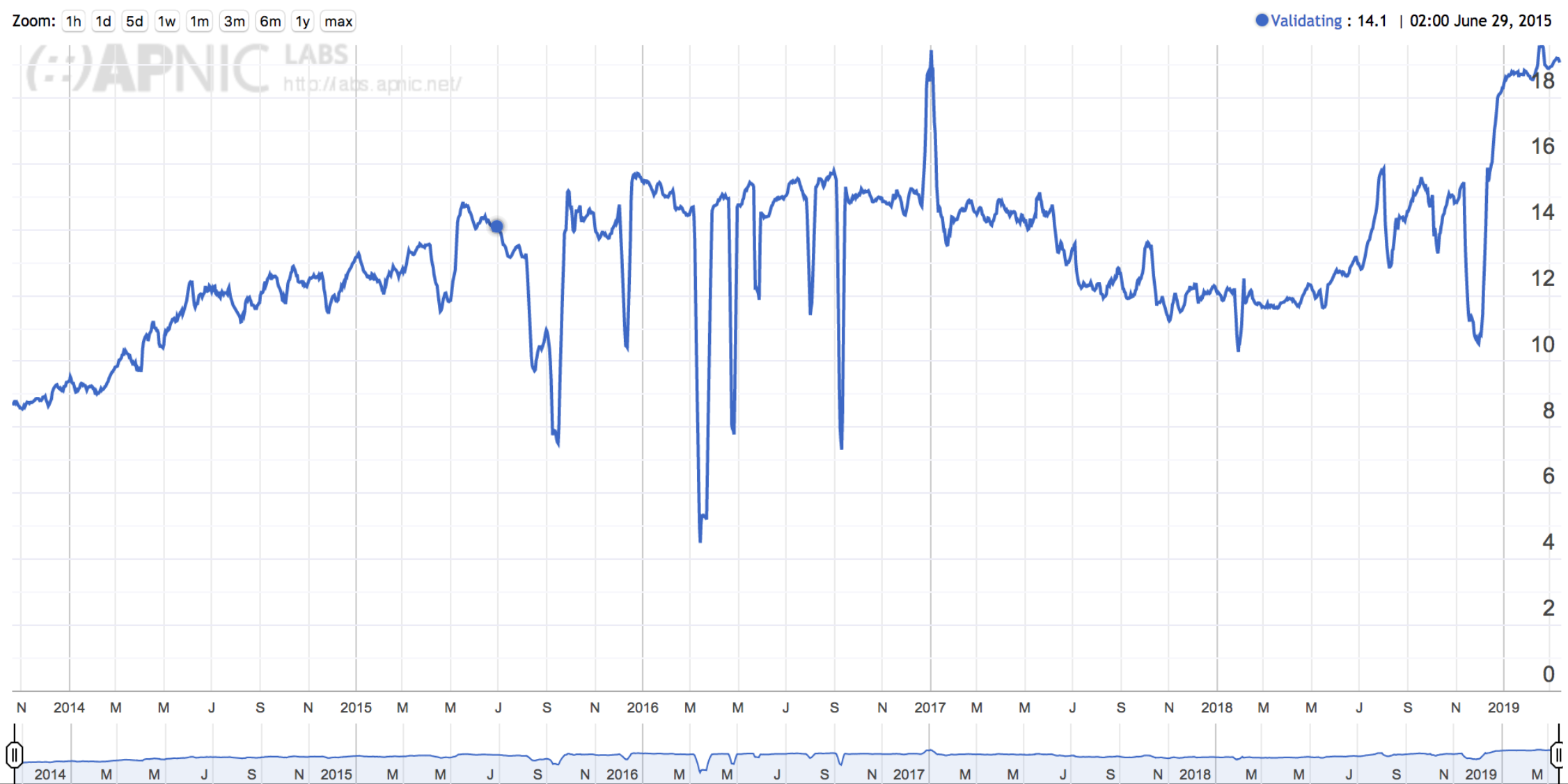

- Deploy DNSSEC (both signing zones and validating responses)

If you’re an owner of a domain name, you should in any case set up a DNSSEC for your domain.

Such security ensures end users are connecting to the actual web site or other service corresponding to a particular domain name. ICANN says “Although this will not solve all the security problems of the Internet, it does protect a critical piece of it - the directory lookup

But what is DNSSEC exactly? To quote the ICANN DNSSEC – What Is It and Why Is It Important? :

With DNSSEC, it’s not DNS queries and responses themselves that are cryptographically signed, but rather DNSdata itself is signed by the owner of the data.

In a nutshell, It adds two important features to the DNS protocol, the first one is the data origin authentification that allows a resolver to verify the data received actually came from the zone where it believes the data originated. The second feature is data integrity protection, that ensures that data hasn’t been modified in transit since it was originally signed by the zone owner with the zone’s private key.

According to the Internet Society, there’s only 19,25% of global registrars having deployed DNSSEC, so there’s a long way before it’s becoming a standard, yet, with the DNSpionage attack, ICANN urges adopting DNSSEC now.

But unfortunately, DNSSEC will not solve all issues concerning security threats, yet it’s a part of a solution to reduce surface attack.

- Use registration features like Registry Lock that can help protect domain names records from being changed (VALIDATE A AND NS RECORD CHANGES)

- Use access control lists for applications, Internet traffic and monitoring

- Review accounts with registrars and other providers

- Monitor certificates by monitoring, for example, Certificate Transparency Logs

- Use 2-factor authentication and require it to be used by all relevant users and subcontractor. AS WELL, IMPLEMENT MULTI-FACTOR AUTHENTICATION ON YOUR DOMAIN’S ADMINISTRATION PORTAL.

- Validate the source IPs in OWA/Exchange logs.

For users

- Check the whois or if IP address changed As a normal internet user, spotting a DNS Hijacking is a bit trickier because you have to detect that a whois of a domain name changed. Which is not so easy for non-technical people. To be honest with you, there’s absolutely no way to protect yourself from the attack that happened (DNSpionage), because the source is controlled. Yet, it is unthinkable to check always if the whois changed for each website we log in, the user experience would be terrible. Always put in doubt any website you visit, if you think that there is something not clear, go away.

Going further on the attack…

If you understood all the explanation above and you still curious to get more technical information, you can check:

Talos’s repor

CrowdStrike report

KrebsOnSecurity article

Glossary

Host file: The host file contains Domaine Name and IP address associated with them. Changing the file may result to point to some other fake page.

DNS Hijacking: It occurs when a bad actor hijacks DNS addresses and reroute traffic toward a malicious server (could be a malicious webpage).

DNS Spoofing: It refers to the broad category of attacks that spoof DNS records. It is a category of attacks (an end goal of the attack, rather than a particular attack mechanism).

DNS Pharming: “Pharming” is a neologism based on the words “farming” and “phishing”. It consists to poison a DNS server which causes multiple users to inadvertently visit the malicious website. Another variant of this attack is to infect a user through a malware (Trojan for example), modifying its host file ( = DNS cache poisoning) in order to redirect away from the intended target toward a fake website.

DNS Cache Poisoning: It is one way to do DNS Spoofing. It consists to change the cache (the host file). It can be done locally and remotely by an attacker.

DNSSEC: Domain Name System Security Extensions strengthens authentification in DNS using digital signatures based on public key cryptography.

Sources

https://www.crowdstrike.com/blog/widespread-dns-hijacking-activity-targets-multiple-sectors/

https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2019/01/global-dns-hijacking-campaign-dns-record-manipulation-at-scale.html

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2019/02/a-deep-dive-on-the-recent-widespread-dns-hijacking-attacks/

https://dribbble.com/shots/3756030-DNS-Records-explained

https://dribbble.com/shots/5307225-DNSSEC

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_Name_System_Security_Extensions

http://breakthesecurity.cysecurity.org/2011/08/what-is-pharming-attack-dns-poisoning.html

https://www.kaspersky.com/resource-center/definitions/pharming

https://www.howtogeek.com/161808/htg-explains-what-is-dns-cache-poisoning/

https://techcrunch.com/2019/02/23/icann-ongoing-attacks-dns/